5 Tips to Creating and Maintaining Classroom Expectations

The First Step of Teaching Self-Monitoring and

Implementation of The Self & Match System

Educators have long known the wide-range of variables that impact the behavioral success of our students. Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, the majority of students were educated in-person; learning classwide expectations from their teachers and peers from a young age. During virtual instruction throughout the pandemic, some of our “tried and true” classroom strategies to help students learn how to be successful were derailed in numerous ways due to the sudden and extreme shift in our instructional modalities and the necessity to quickly pivot to a virtual format.

As we return to brick & mortar learning, it is clear that the behaviors displayed in many classrooms has become even greater, given that student experiences ranged dramatically throughout their time in distance learning. Without a doubt, behavioral expectations throughout distance learning varied greatly in homes given each family’s unique circumstances. As a result, children have returned to “in-person” instruction demonstrating a variety of social, behavioral, and academic skills/needs. Not to mention, the majority of students who are currently enrolled in grades K-2 have never experienced a full “typical” year of elementary school. Many of them had their preschool experience flipped upside down! Preschool and early elementary is a developmental time where students often learn school readiness and behavioral/social group interactions. Yet many children missed that opportunity due to the necessity to learn at home. As a result of these various factors, many classrooms around the globe are experiencing higher rates of behavioral challenges than pre-pandemic levels (1).

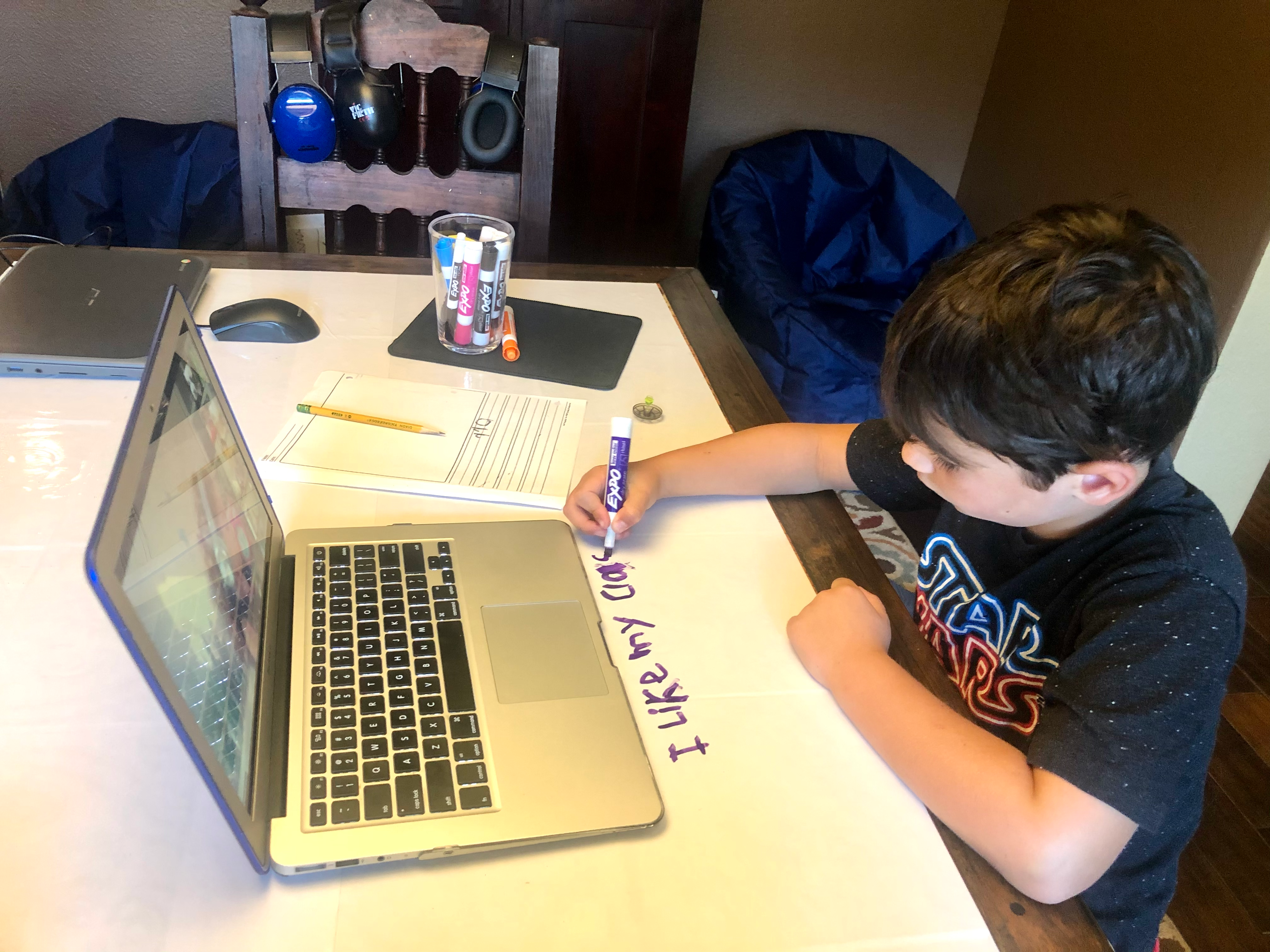

One simple way to support our student’s behavioral success as they return to in-class learning is to prioritize setting clear expectations and then systematically teaching our students the tools needed to self-monitor their behavior(s) to match these expectations using Self & Match. All students thrive on having expectations and the value of setting clear classroom expectations has been researched for over 70 years (2). So, let’s take a look at some key tips to setting up effective classroom expectations as well as tools to teach self-monitoring as we go back to the basics and prepare our students to be successful, lifelong learners.

5 Tips to Consider as You Set Classroom Expectations With Your Students and Develop your Self & Match Systems:

1) Create 3-5 clear/explicit class expectations that are stated positively.

Set expectations of what you would like your student to do (i.e. “Be Responsible by coming to class on time”) rather than what you don’t want your student to do (i.e. “Don’t Come to Class Late”). (3)

2) Make the expectations easy to remember, simple to understand, age-appropriate, and enforceable.

Ensure that all students can identify the class expectations and, if possible, explain them in their own words. Consider incorporating visuals and teach examples and non-examples that align with each expectation. Remember to use language that is familiar to your students, make it fun, tied to your classroom themes, school-wide PBIS culture, and (if applicable) your Self & Match Questions! For example, if you have a space themed classroom, using terms like “Out of this world!” might be language to reinforce the expectations and connect for your students. (4)

3) If possible, co-construct the expectations with your students and allow them to have a voice in the process of creating and setting expectations.

If a class expectation is to “Be Kind”, ask your students what “Being Kind” means to them and include the student definitions on the clearly posted expectations within the classroom. Allow students to develop clear examples and non-examples of the class expectations and remember that the examples can be added to or modified throughout the year. Including example(s) and non-examples increases the rate at which students follow through with classroom expectations (5).

Go further than simply posting the expectations in a visible location by referencing them frequently, make it a part of your daily schedule, and (if applicable) review at each Self & Match check-in opportunity. Infuse the language of the expectations throughout your school day by catching students engaging in the class expectation and reinforcing/labelling it (i.e. - “Kai, I love the way you are Following Directions by starting your classwork”).

5) Empower students to take ownership and responsibility for their own behavior. Recognizing expectations is the first step of teaching self-monitoring within an educational setting.

In its simplest terms, self-management involves the personal/self-application of behavior-change procedures that supports goal achievement. How can we expect students to accurately reflect on their behavior, if they do not have a clear understanding of the expectations? This is why it is critical that the first step you take is establishing classroom expectations with your students.

Taking it a step further...

HOW CAN I SET-UP A SELF & MATCH SYSTEM TO FURTHER ENHANCE SELF- AWARENESS OF CLASS EXPECTATIONS

As we are returning to our physical classrooms amidst the pandemic, teachers are looking to add additional user-friendly tools to their toolkit in order to promote the behavioral success of our students. The Self & Match System is a tool that many educators and practitioners have turned to to implement individually or class-wide.

The Self & Match System is a self-management and motivational system firmly grounded in principles of Applied Behavior Analysis (ABA). This manualized behavioral intervention encourages a collaborative approach to promoting systematic behavioral success for children and young adults using self-monitoring with an accountability/match component. Systematic planning before beginning an intervention makes a world of difference and is a fundamental element of the Self & Match system. Each system is individually developed using a comprehensive “considerations guide” that is included in the Self & Match manual.

Self & Match has been implemented internationally across a variety of settings including: special and general education classrooms; homes; sports programs; camps; clinics; as well as public, private, parochial schools, post-secondary education.

The 6th edition of The Self & Match System: Systematic Use of Self-Monitoring as a Behavior Intervention includes all the materials necessary to guide the development and implementation of individualized Self & Match Systems. Included in the manual is a forward by a trailblazer in the ABA world, Dr. Saul Axelrod; an introduction that provides a review of the literature supporting self-monitoring; a “Considerations Prior to Implementation Guide”; 20 sample Self & Match forms, five reproducible Self & Match forms; and an assortment of supplemental materials. The manual also includes access to an online portal of customizable digital forms and a PDF form creator called the “Self & Match Maker”.

Our ultimate goal is to provide you with practical tools to help students monitor and reflect on their own behavior so that they can become more independent and self-determined, resulting in an improved quality of life!

Want to learn even more about the Who’s, What’s Where’s, Why’s, When’s, and How’s of Self-Monitoring interventions? Check out our 2018 DRL blog here

About The Authors

Jamie Salter, Ed.S., BCBA

Jamie S. Salter, Ed.S., BCBA co-authored the Self & Match System; an evidence-based self-monitoring intervention that is grounded in principles of Applied Behavior Analysis. Jamie consults with teams around the globe in the development and implementation of Self & Match interventions as a Tier 1, 2, or 3 behavioral tool within the school, clinic, and home settings.

Previously, Jamie served for a decade as a Senior Program Specialist at the San Diego County Office of Education. In her role, she trained educators on writing effective and legally-defensible Behavior Intervention Plans, provided leadership and guidance to special educators, consulted with teams utilizing the Self & Match system, and supported students, families, and IEP teams in determining appropriate programs for students in their least-restrictive environment. Jamie has been actively involved in supporting children with autism for over 20 years. These experiences include serving as Supervisor of an U.S. Department of Education Training Grant (focused on inclusion of students with low incidence disabilities) and presenter at multiple International Conferences. She has also operated a school-based clinic that provided an emphasis on Intensive Behavioral Interventions, led social skills groups, sibling support groups, and provided in-home behavioral intervention. She has served on the state-wide PENT Cadre Leadership team since 2016. Jamie received her Masters of Education, Educational Specialist degree, Nationally Certified School Psychologist status, and BCBA certification through Lehigh University.

Katharine Croce, Ed.D., BCBA

Dr. Katharine Croce is a Board Certified Behavior Analyst-Doctoral (BCBA-D). Dr. Croce received her Doctorate in Educational Leadership at Saint Joseph’s University in Philadelphia. Dr. Croce earned a MS. Ed., in Applied Behavior Analysis from Temple University, a BA in Psychology and Criminal Justice from La Salle University, and an Autism Certificate from Pennsylvania State University.

Dr. Croce is an Assistant Professor in the School of Education at Felician University teaching undergraduate and graduate courses in Applied Behavior Analysis. Previously, Dr. Croce was the Director of the ASERT Collaborative Eastern Region at Drexel University. ASERT (Autism Services, Education, Resources and Training) and brings together autism resources (locally, regionally, and statewide) to improve access to quality services and information, provide support to individuals with autism and caregivers, train professionals in best practices and facilitate the connection between individuals, families, professionals and providers.

Dr. Croce has worked as a Special Education Coordinator and behavior analyst in public/private schools, home settings, and an in-patient hospital for children with autism spectrum disorders (ASD) and other developmental disabilities. Dr. Croce has also worked in a clinic setting developing programs for individuals with ASD, a support program for college students with ASD, and training undergraduate and graduate education and psychology majors who wanted to work in the field of ASD.

Contact Jamie or Katie at selfandmatch@gmail.com

- National Association of School Psychologists. (2020). Providing effective social–emotional and behavioral supports after COVID-19 closures: Universal screening and Tier 1 interventions [handout].

- Zimmerman, E. H., & Zimmerman, J. (1962). The alteration of behavior in an elementary classroom. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior, 5, 50-60.

- Burden, P. (2006). Classroom management: Creating a successful K-12 learning community. (3rd ed.). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

- Grossman, H. (2004). Classroom behavior management for diverse and inclusive schools. (3rd ed.). New York: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc.

Kerr, M. M., & Nelson, C. M. (2010). Strategies for addressing behavior problems in the classroom. (6th Ed.). Columbus OH: Merrill.

Burden, P. (2006). Classroom management: Creating a successful K-12 learning community. (3rd ed.). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

- Neef, N. A., Shafer, M. S., Egel, A. L., Cataldo, M. F., & Parrish, J. M. (1983). The class specific effects of compliance training with ―do‖ and ―don’t‖ requests; analogue analysis and class-room application. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 16(1), 81-99.

-

We are Teachers (2021). The last normal school year. https://www.facebook.com/WeAreTeachers/photos/a.10150774463388708/10159925416488708/?comment_id=10159925712753708. September 27, 2021